Designing a Digital Co-Instructor for Enhanced Reading Engagement

The Problem

In an era dominated by digital media and fragmented content consumption, sustained reading habits are in decline globally. As students increasingly engage with short-form, screen-based text, their ability to read deeply, critically, and fluently has weakened. This shift is mirrored in Indonesia, where PISA scores in reading have steadily declined over the past decade — placing the country among the lowest-performing globally. Despite curriculum reforms, reading instruction in Indonesian classrooms has remained largely static, leaving teachers under-equipped to address the evolving cognitive demands of deep reading in the digital age.

PRAXIS is designed to scaffold planning and implementing evidence-based reading engagement instruction.

With features like thematic unit builders, drag-and-drop lesson building, modeled comprehension strategies, and embedded teaching prompts, PRAXIS helps teachers internalize effective practices through guided doing instead of PD training modules.

When co-designed with teachers, a platform like PRAXIS serves not only to apply what works, but to uncover what works better.

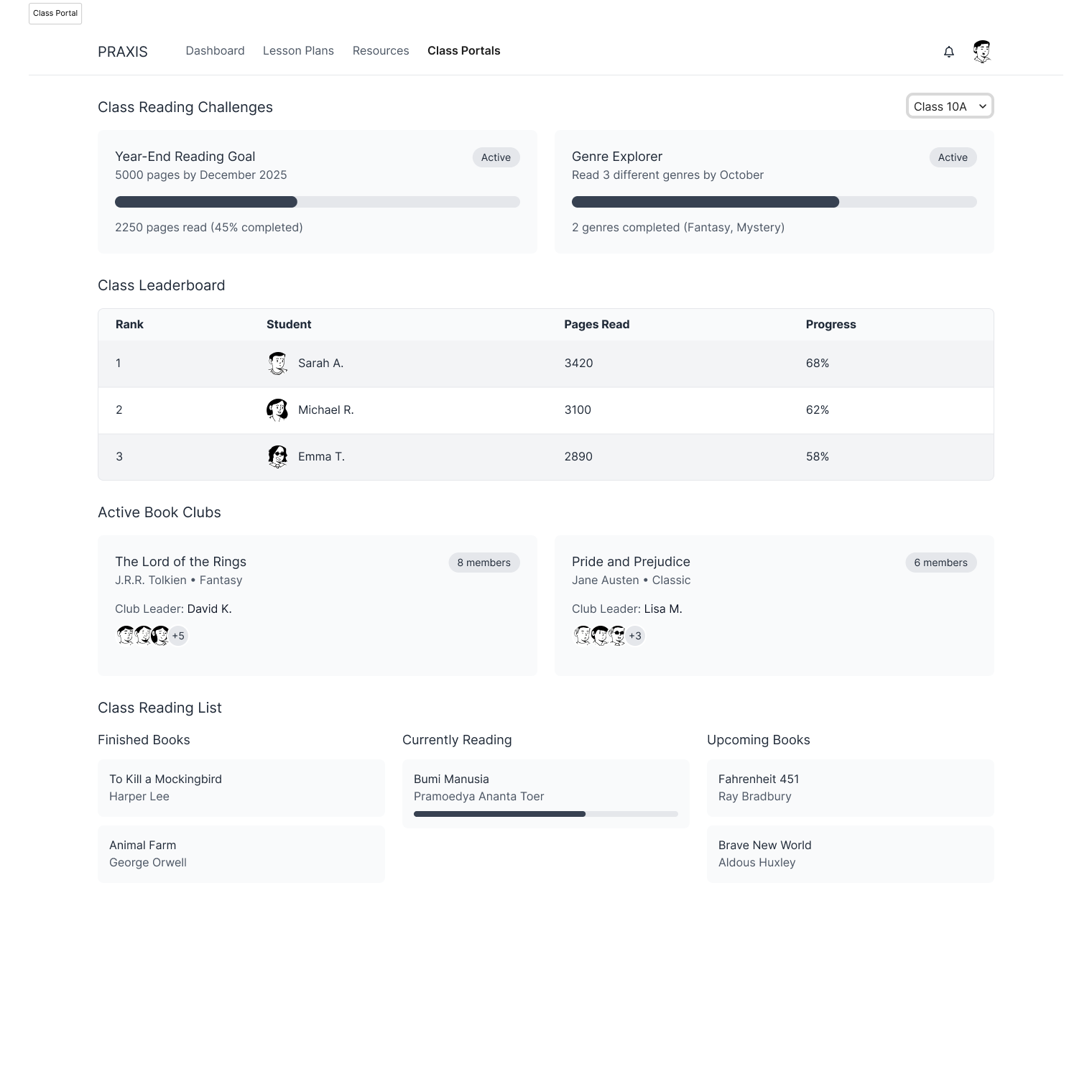

PRAXIS also bridges formal instruction with informal, interest-driven reading.

Teachers can create reading challenges, launch book clubs, and track participation — cultivating a learning environment where reading is meaningful and socially valued.

✺ Theory of Change: When students are given meaningful reasons to read through choice, collaboration, and personal relevance, they engage more frequently and with greater intention. Over time, this sustained engagement builds reading fluency by increasing exposure to complex texts, expanding vocabulary, and strengthening cognitive stamina. As fluency improves, students are better able to allocate attention to making inferences, analyzing structure, and connecting ideas — deepening comprehension. This, in turn, reinforces motivation and confidence, creating a positive feedback loop. ✺

the design of PRAXIS is informed by:

Anderson, R. C. (2018). Role of the Reader's Schema in Comprehension, Learning, and Memory. In Theoretical models and processes of literacy (pp. 136-145). Routledge.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive Apprenticeship: Teaching the Craft of Reading, Writing, and Mathematics. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing, Learning, and Instruction: Essays in Honor of Robert Glaser (pp. 453–494). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dehaene, S. (2010). Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read. Penguin Books.

Guthrie, J. T., Klauda, S. L., & Ho, A. N. (2013). Modeling the Relationships Among Reading Instruction, Motivation, Engagement, and Achievement for Adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(1), 9–26.

Lee, Y., Jang, B. G., & Smith, K. C. (2021). A Systematic Review of Reading Engagement Research: What Do We Mean, What Do We Know, and Where Do We Need to Go? Reading Psychology, 42(5), 1–37.

RAND Reading Study Group, & Snow, C. (2002). Defining Comprehension. In Reading for Understanding: Toward an R&D Program in Reading Comprehension (pp. 11–18). RAND Corporation.

Wigfield, A., Guthrie, J. T., Perencevich, K. C., Taboada, A., Klauda, S. L., McRae, A., & Barbosa, P. (2008). Role of Reading Engagement in Mediating Effects of Reading Comprehension Instruction on Reading Outcomes. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 432–445.

Wolf, M. (2019). Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World. Harper.